Cohort studies take time, particularly when looking at cancer as an outcome of interest. It will be several years before the ABC Study has collected enough data to begin analysing them. Data from our older cohort study, Health2020, has been used recently in an analysis examining physical activity as a strategy to reduce the risk of developing cancer.

Health2020 is a prospective cohort study started by Cancer Council Victoria in 1990. It is part of the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Cohort Consortium, a collaboration between studies and researchers from all over the world that pools anonymised data to definitively answer key questions in cancer epidemiology.

Associate Professor Brigid Lynch, Deputy Head of the Cancer Epidemiology Division, and Professor Roger Milne, Head of Division, recently worked with colleagues from the U.S. and Europe on a ground-breaking Cohort Consortium study of physical activity and cancer. Nine cohort studies collected detailed information about the frequency, duration and intensity of physical activity, which allowed us to investigate trends in the relationships between physical activity and risk of several different cancers.

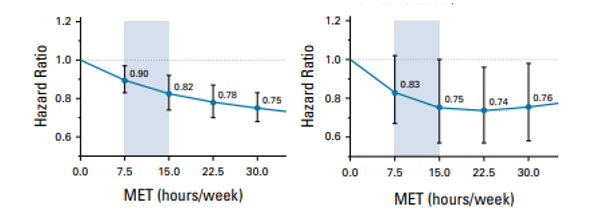

A pooled total of 755,459 study participants had been followed for 10 years, during which 50,620 cancers were diagnosed. Dose-response relationships were identified between physical activity and risk of numerous cancers. For these five cancers (breast, colon, endometrial, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, and head/neck), as the amount of physical activity increased, the risk went down, and engaging in more than the recommended level of physical activity (i.e. more than 150 minutes per week) was associated with further risk reduction (see example in Figure 1). In contrast, the relationship between physical activity and kidney, gastric cardia, liver cancer and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was curvilinear – that is, there was a plateau in risk reduction at higher levels of physical activity (see example in Figure 1). For these sites, there appeared to be no additional benefit in exceeding recommended physical activity levels.

Examining the patterns in the relationship between physical activity and cancer risk is important, because seeing a clear linear (or curvilinear) trend suggests a biological dose-response (an indication that the relationship is causal). Knowing that physical inactivity causes cancer means we can make strong public health recommendations promoting physical activity to reduce cancer risk. The findings from this study also provide insight into the amount of physical activity needed for a reduced risk for different cancer types.

Figure 1. An example of a linear dose-response (left) and a curvilinear dose-response (right). MET hours/week is a measure of the frequency, duration and intensity of physical activity. Half an hour of brisk walking, five times per week is equivalent to about 7.5 MET hours/week. The shaded blue bar in these charts is the amount of physical activity typically recommended by public health guidelines. For some cancers, doing more activity than recommended provides additional risk reduction (left), whereas there is no additional risk reduction gained for other sites (right).

Reference: Matthews CE, Moore SC, Arem H et al . Amount and intensity of leisure-time physical activity and lower cancer risk . J Clin Oncol. 2020; 38(7):686-697. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.19.02407

View more latest news